The North Atlantic Ocean Current May be Slowing

“We are 50 to 100 years ahead of schedule with the slowdown of this ocean circulation pattern,” says climate scientist Michael Mann.

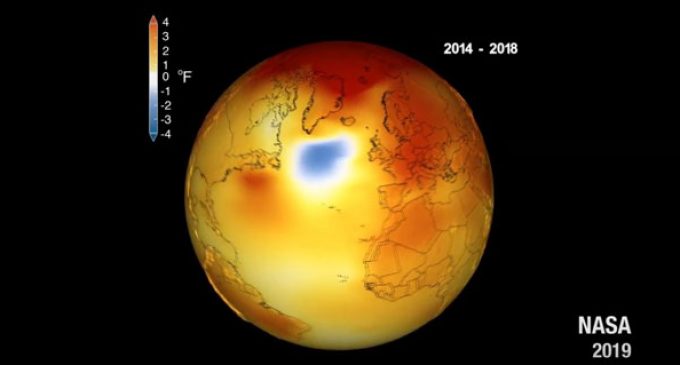

A stubborn blue spot of cool ocean temperatures stands out like the proverbial sore thumb in a recent NASA image of the warming world – a circle of cool blue on a planet increasingly shaded in hot red.

A region of the North Atlantic south of Greenland has experienced some of its coldest temperatures on record in recent years, a cooling unprecedented in the past thousand years. What explains that anomaly?

Climatologist Michael Mann of Penn State University, in this month’s “This is Not Cool” video, explains that this phenomenon may be an indication that the North Atlantic current, part of a larger global ocean circulation, is slowing down.

This current played a role in the 2004 science fiction movie ‘The Day After Tomorrow’, a film that was “based on science, but greatly overblown” and that therefore “frustrated a lot of climatologists,” Jason Box of the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland points out.

Stefan Rahmstorf of the University of Potsdam, Germany, says this circulation – called the thermohaline circulation, but popularly known to many in the U.S. as ‘the Gulf Stream’ – keeps northern Europe several degrees warmer than it would otherwise be at that latitude.

Although the movie’s disaster plot was pure science fiction, the consequences of a shutdown would be serious for agriculture – and for temperate weather – in northern Europe.

The current depends on the saltiness of the North Atlantic to create the sinking motion of water, that is, it’s the “pump” driving the current. Saltier water is heavier than fresh water.

As the Greenland ice sheet melts, large volumes of fresh water enter the North Atlantic and freshen the very salty sea water, slowing the ‘pump’, Jorgen Peder Steffensen of the University of Copenhagen explains in the video, produced for Yale Climate Connections by independent videographer Peter Sinclair of Midland, Michigan.

“That would make it terribly cold in Denmark, where I come from,” Steffensen says. “In principle, there’s no reason why Earth could not get warmer but still northern Europe and North America could get cold. Still, that area is not large compared to the global area.”

Melting ice from Greenland largely explains the freshening North Atlantic, Box agrees.

“We are 50 to a hundred years ahead of schedule with the slowdown of this ocean circulation pattern, relative to the models,” according to Mann. “The more observations we get, the more sophisticated our models become, the more we’re learning that things can happen faster, and with a greater magnitude, than we predicted just years ago.”